Motorcycles were having a time at the start of the 20th century. As mankind hurtled towards and through the Industrial Revolution, man and machine were becoming more well-established as a pairing, and ways to transport ourselves and goods in less time and more easily were quickly being established and refined. But that’s not to say motorized vehicles were not fun either. Many motorcycles started with humble beginnings as bicycles with an engine earnestly slapped to the bar and strategically wired to help give riders an extra little push to putter along the dirt or cobblestone streets that existed until the first paved road came along many years later. But a little dirt never stopped riders. In fact, they were taking to the dirt and board tracks of those days without abandon—pushing the limits early on of man and machine, long before the automobile really could.

The 10 iconic motorcycles listed on this near century-long timeline are not only models on offer (without reserve) as part of the Dare to Dream Collection—they each have a notable place in the two-wheeled timeline, where they changed what could be for the rest of the machines listed, pushing the limits of engineering far beyond what anyone thought capable, and many influencing the bikes that came up to iconic status sometime after. They’re each a testament to engineering brilliance and innovation.

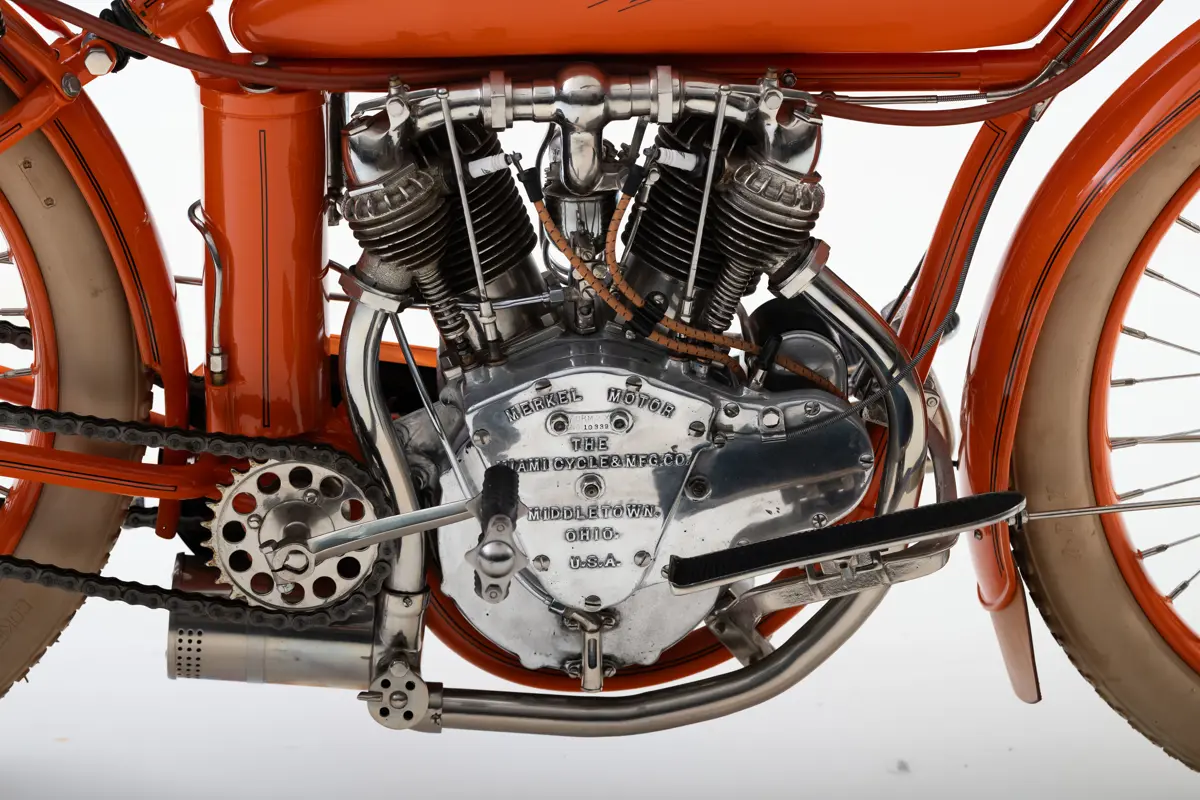

Flying Merkel Model 471

The first-ever American superbike debuted over a century ago in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. If you’re thinking of one orange and black-liveried company by the name of Harley-Davidson, you’d be incorrect. Credit is actually owed to a smaller motorcycle manufacturer, also bearing orange and black, born there known as Merkel Motorcycles. Joseph Merkel, considered one of the finest motorcycle engineers of his time, started the 20th century by adding motors to pedal bicycles before working on building his very first motorcycle. By the end of the decade, he had created the bike that bike manufacturers strived to build or utilized for inspiration. The Flying Merkel was born capable of reaching speeds of 96 mph! For reference, road model automobiles in the 1910s were able to surpass 50 mph and barely breach 70 mph. But speed was king and would prove beneficial advertising for Merkel, as board and dirt track riders’ victories would bring astounding attention to the manufacturer.

The Flying Merkel Model 471 was powered with a 471 V-twin, mated to a single-speed transmission, chain-driven to the rear wheel, or could be optioned to be belt-driven. What truly made the Flying Merkel special was its ride though, considered one of the smoothest (and fastest) of its days. The front and rear suspension on the Merkels were incredibly unique and often considered revolutionary. The front fork appeared telescopic using dual coil springs, while the rear suspension was a mono-shock design, which was later duplicated and used by many other motorcycle manufacturers, including Yamaha, in builds beyond the lifespan of the Merkel Motorcycle company.

Indian Four

For many riding enthusiasts, when the Indian brand comes up, the first few things that may come to mind are that it is the oldest motorcycle brand in America and its Chief and Scout models. But the true Indian fans know about the most important bike of the brand’s history—the Indian Four.

It was once Indian’s four-cylinder flagship touring motorcycle, considered the Duesenberg of motorcycles. But at the time, Indian didn’t have a four-cylinder they built in-house, so they looked to a place that did: Ace Motor Corporation of Philadelphia. Ace had been building four-cylinder engines since William Henderson had been in partnership with his brother for their company, the Henderson Motorcycle Company. Henderson had been building four-cylinders since 1911, and when the company was sold, William went on to form Ace, and the four-cylinder engine developed was further refined there until William’s unexpected death. Ace began faltering, and Indian swooped in to save the company. The pairing would prove beneficial to both in building the ultimate luxury tourer.

The Indian Ace was introduced in 1936, featuring an exhaust-over-inlet for its cylinder heads. When that configuration didn’t quite work, Indian returned to the drawing board to do the inlet-over-exhaust for 1938. The result was successful, and the 78 cubic-inch engine, mated to a three-speed gearbox for 44 horsepower would be a mainstay in the Indian lineup as the Indian Four. Five-thousand Indian Fours would be built from its introduction in 1938 until the outbreak of World War II, and the production of the four-cylinder engine, and thus the Four, ended in 1942.

Harley-Davidson EL ‘Knucklehead’

While Indian was enjoying the successes of the Indian Four, Harley-Davidson would soon pull ahead in popularity with its new, official production overhead valve V-twin. Introduced in the middle of the Great Depression, 1936, it was coined the “Knucklehead” for its valve covers’ fist-like shape, and offering more power and speed than its previous models and competitors’ models. It would be the engine that set a new speed record of 136.183 miles per hour at Daytona Beach, and would launch Harley-Davidson to the top as the premier motorcycling company. The Knucklehead would eventually evolve into a 74 cubic-inch engine, and be utilized heavily for military bikes in World War II. Knucklehead production would end shortly after though, in 1948, when Harley introduced the Panhead as its replacement. However, the Knucklehead would live on as a framework for some of the engines still produced and utilized on Harley-Davidsons today.

Vincent HRD Black Shadow Series C

Following the dark days of World War II, as Harley-Davidson would also experience in the States, many manufacturers found themselves in a difficult spot, as wartime rations were still affecting their ability to resource raw materials. Steel was nearly impossible to obtain, but there was an abundance of aluminum. It was a problem even British motorcycle manufacturer Vincent-HRD found itself facing in its return to building bikes. It, like other manufacturers, were forced to find creative alternatives to making their machines work with other materials, like aluminum for steel where necessary, but it meant machines could be built again.

Vincent would produce a post-war bike, first the Series B Rapide, before introducing the Black Shadow Series C just a couple of years later. The Series C certainly made use of unique sourcing and innovation—like borrowing the idea of a hollow sheet-steel backbone for the frame, originally used by the American Flying Merkel, which also doubled as an oil tank.

Its most renowned and iconic characteristic though, was its speed. In 1948, a top speed of 125 mph was incredibly impressive for a motorbike. This was thanks to the Black Shadow’s 998 cubic-centimeter 50-degree V-twin engine, good for 55 horsepower. Yet with great speed comes great responsibility, and this particular Vincent with its “darkly romantic reputation,” made it an avoidable model for some, or the most desirable bike to own—its “widowmaking” ways be damned. While some took the words written by Hunter S. Thompson to heart in his ‘90s review of the Black Shadow in Cycle World, others were piqued by renowned automotive and motorcycle journalist Peter Egan’s review of the bike in a 1998 Cycle World issue, where he wrote that the Black Shadow was “...solid as a brick, unfazed by switchbacks, dips, roller-coaster hilltops, fast sweepers or bumpy mid-speed corners [...] It is honestly one of the nicest-handling bikes I’ve ridden, neutral and instinctive on turn-in and lean.” Regardless, the bike remains iconic for what it was able to achieve in a time when everything was rather replete and depressing and remains a fascinating precursor to what would eventually become the superbike craze decades later.

Norton Commando 850 Roadster

Most riders are familiar with the Norton Commando and its most iconic black and gold livery. Its beginnings were stoked by a fire to compete with Japanese manufacturers, and Norton-Villers Chairman Dennis Poore wanted a new flagship model made in order to do it. A design team was formed with former Rolls-Royce engineer Dr. Stefan Bauer at the head of the table, working alongside former Velocette engineer Charles Udall to begin work on what would eventually become the Norton Commando.

The cafe-style bike first debuted as an incredibly successful and desirable 750 cubic-centimeter model, winning Motor Cycle News’ “Machine of the Year” five consecutive years running. The 850 would ride through this success, albeit briefly. The larger displacement model featured a new, 828 cubic-centimeter motor with a larger bore and through-bolted cylinder block, paired with a stronger gearbox and all-metal clutch. Norton unfortunately would have to close its doors in 1978, unexpectedly making the larger Commando the swan song to the final days of Norton’s motorcycle manufacturing.

1978 Yamaha TZ750

Motorcyclist magazine deemed the Yamaha TZ750 the “most notorious and successful road-racing motorcycle of the 1970s,” which argues quite fairly why this motorcycle would be part of this iconic list. Yamaha was aiming to build a larger bike, in tandem with its YZR500, with hopes of taking the larger 700 cubic-centimeter bike to compete in the Formula 750. To make an engine close to that size, Yamaha started with two of its liquid-cooled, inline 2-cylinder TZ350 engines put together to make a 700 cubic-centimeter inline four-cylinder engine. The resulting engine, further refined, would be a 747 cubic-centimeter two-stroke, inline four-cylinder engine rated at 120 horsepower.

What really cemented the TZ750’s place in history was its winning pedigree. Yamaha would make an intriguing offer to Italian world champion rider Giacomo Agostini to ride the new factory spec TZ750. “Ago” as he was affectionately called, would win the 750’s debut race at the Daytona 200-mile race. Yamaha would go on to win the next eight AMA Daytona 200 races.

Suzuki RGB500 Gamma

In 1969, Suzuki made a decision to walk away from motorcycle grand prix racing for a brief stint, after the Fédération International de Motocyclisme, or FIM, implemented new rules to bring down costs for both works and non-works teams—effectively limiting the types of bikes that could be entered. Manufacturers Honda and Yamaha also joined Suzuki in walking out of the series. Suzuki was still interested in racing, and after a cooling-down period returned, introducing a worthy fighter to the circuits. What emerged was the RG500, considered an “unorthodox 500 cubic-centimeter, square-four, two-stroke engine producing an excess of 100 horsepower,” which nabbed podium finishes in the first two years of its run in FIM’s 500 cc class (1974 and 1975). Additional finessing of the RG500, including an anti-dive fork that would keep the bike level under braking, landed Suzuki the 1976 and 1977 World Championships with rider Barry Sheene.

The Gamma version of the RG500, the RGB500, was introduced in 1981 with many more improvements. Suzuki’s signature “Full Floater” rear suspension was now in use, where a single, vertical shock was mounted near vertically and would work from both ends. The beastly machine gave Suzuki another two 500 cc World Championships for 1981 and 1982, with riders Marco Lucchinelli and Franco Uncini. Gamma would see more improvements made to the engine in 1983 and 1984 to produce an impressive 120 horsepower and land a top speed of 170 mph. A roadgoing replica of this bike would be made as well, from 1984-1987, but a true Gamma was only meant for a circuit’s asphalt.

Honda NR750

When Honda made the decision to reenter the competitive racing world after a 12-year hiatus, it of course did so in its own way. At a time when the two-stroke bike was dominating the racing world, Honda went in a different direction to develop a four-stroke 500 cubic-centimeter contender. The Japanese manufacturer found itself proven wrong with its first iteration, the NR500, that just couldn’t get over the hurdles of engine issues. So, Honda gave into making a two-stroke, for the time being, the NS500.

But the four-stroke 500 cubic-centimeter engine project hadn’t been benched for good. Honda continued to develop this odd engine, now a 747 cubic-centimeter four-stroke with oval cylinders and twin titanium connecting rods with eight valves per cylinder—essentially a V-4 that functioned like a V-8, putting out a hefty 125 horsepower. Weighing in at only 491 pounds dry, Honda utilized lightweight carbon fiber panels, cast magnesium wheels, side-mounted radiators, and exhaust outlets exiting under the seat. This was Honda’s superbike masterpiece, with only 322 produced from 1992-1994. The cost certainly reflected its power and exclusivity, earning itself the title of the most expensive production model in the world at the time and priced at $50,000 new.

Ducati 996R

Ducati’s 996R story really begins with the 916 back in 1994. Designed by Massimo Tamburini, the 916 would go on to win four Superbike World Championships by 1998, laying the foundation to become the blueprint for superbikes going forward. In 1999, Ducati introduced the next iteration of the 916—the 996—although very little was changed between the two models outside of the exhaust was now mounted below the seat for improved aerodynamics, and a single-sided swingarm-mounted rear wheel was designed for faster wheel changes in races.

Its ultimate form would debut in 2001 as the 996R—the “R” standing for “racing”—featuring multiple upgrades including carbon fiber bodywork, revised fairings, Öhlins front and rear suspension, and the Testastretta engine, designed under the care of former Ferrari Formula 1 engineer Angiolino Marchetti. The Testastretta “narrow-head” engine was named for its narrow valve arrangement that actually improved combustion. It also featured more aggressive camshafts, titanium connecting rods, and a shorter stroke with a wider bore, allowing it to rev more safely at higher RPMs. Ducati would release a limited series production of 500 996Rs for private customers.

Honorable Mention:

Lotus C-01 “John Player Special”

A few things may come to mind when contemplating why this particular bike stands as an icon. To begin with, the Lotus name itself already lends a certain majesty. The other might be its iconic livery, the “John Player Special.” But there’s another hidden gem to this treasure that also lends to the iconic legacy of this bike. If its stylings are familiar, you may know them to be associated with Daniel Simon, the designer of the Light cycle for TRON: Legacy.

This motorcycle’s origin story was originally thought to be a ruse by Lotus—a “look at what we’re capable of doing” design exercise with Simon for a bike that would never see the light of day. Lotus further surprised fans when it committed to producing 100 of these bikes. However, as suspected, Lotus did not build the bikes. The name was licensed to a German race car constructor by Kodewa, whom they had worked with in competition before, and engineering was fielded by Kalex, with a proven track record of making championship-winning chassis for the Moto2 World Championship series. Powering this lightweight cycle of the future, which dry weighed around 400 pounds, is the V-twin engine from the KTM RC8R, good for nearly 200 horsepower. Customers could option their bikes with a “range of liveries that paid tribute to the great racing cars of the past,” including Martini Racing, all for the humble price tag of $140,000.

2014 BMW S1000RR

When BMW made the decision to return to racing in the 1990s, it wanted to come in with some flare, and it certainly did. In 1992, it introduced the R1 racing prototype—a water-cooled, DOHC boxer-twin engine with Ducati’s hallmark desmodromic valve actuation, resulting in a displacement of 996 cubic-centimeters. The success of the R1 in road racing helped revive the BMW Motorrad program by the year 2000, taking 1990’s 30,000 BMW sales a year and turning that into 90,000 for the year by the turn of the century.

Unfortunately, BMW found itself limited in the further development of the R1’s boxer twin, and it was back to the drawing board. The need for a new engine proved quite beneficial to the German manufacturer, as it debuted its very first superbike in 2009, the S1000RR. Powering the S1000RR was a new, 999 cubic-centimeter inline four-cylinder engine that redlined at 14,200. It gained ABS and traction control, and an optional quick-shifter— handy for clutch-less upshifts without having to roll off the throttle. It was the first of its kind ever found on a motorcycle. BMW upped the ante in 2014 when it introduced Dynamic Traction Control (DTC), where sensors work to control the throttle response and adjust it for appropriate riding conditions when the rear tire is spinning or if the front wheel is lifted off the ground. 2014 also brought BMW another incredible milestone event and win when Michael Dunlop won the Isle of Man TT, making it BMW’s first win in the 75 years the race has been held on the island.

Even with 2014 only being 10 years ago, today, motorcycle manufacturers continue to push the envelope to see what’s next for making rides smoother, easier, more fun, or blistering fast, able to handle the challenging trials of enduro races like the Erzbergrodeo, to the death-defying speeds at the Isle of Man TT competition. The iconic bikes of the future are being engineered or assembled as we speak, ready to take riders down many more roads, especially compared to say, the 1910s. And, at least a lot more of them are also paved.